We are thrilled to host a blog written by members of the TIDE project. TIDE investigates “how mobility in the great age of travel and discovery shaped English perceptions of human identity based on cultural identification and difference.” The following profiles, written by Lauren Working, Emily Stevenson, and Tom Roberts, use our Status Calculator to think through immigrant experience and merchant travel in the period, reflecting on our categories and considering how middling identity fits with nationhood, travel, and social mobility.

A She-Jesuit in Spitalfields (Luisa de Carvajal), by Lauren Working

Turkey Merchant’s Daughter (Joan Staper), by Emily Stevenson

An Englishmen in Italian (John Florio), by Tom Roberts

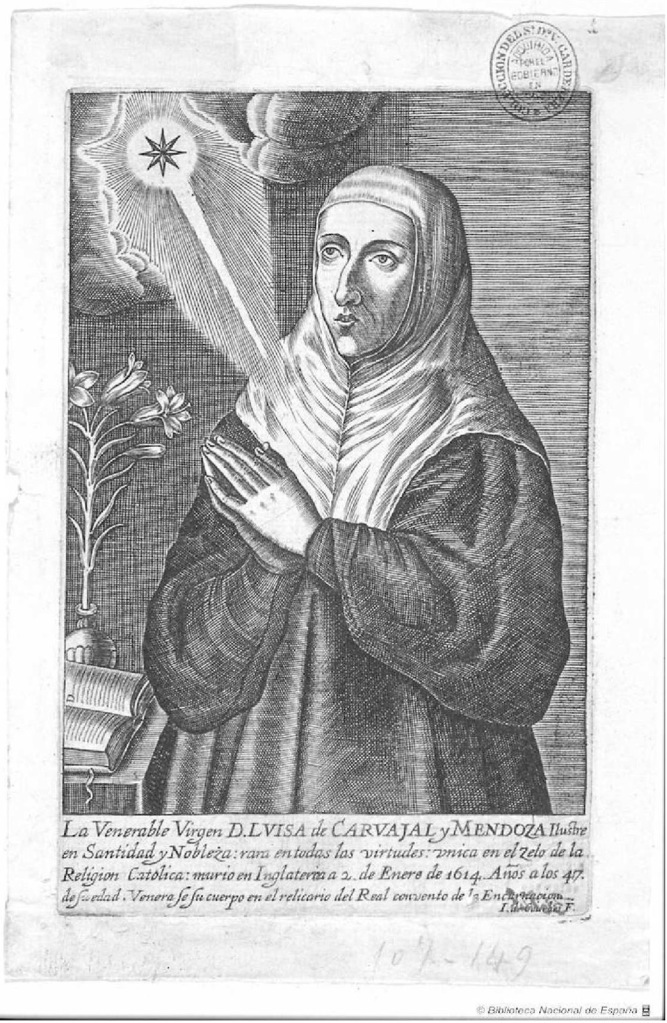

A She-Jesuit in Spitalfields

By Lauren Working

How will the Social Status Calculator place a noblewoman who renounced her wealth, took a vow of poverty and perfection, moved to a new country, and pitted herself against Protestant authority in London? Meet Luisa de Carvajal, a Spanish woman who arrived in London in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, intent on bringing the English back into the fold of the Roman Catholic Church.

What is your gender?

Female

Do you have a title?

No

Carvajal was born into a noble family, but she was orphaned at the age of six. She took a vow of poverty before she moved to London, and never married.

Do you have a coat of arms?

No

Can you write?

I write regularly, though not just for professional/trade purposes.

Carvajal left a spiritual autobiography, mystic poetry, and dozens of letters to prominent English and Spanish Catholics. Her opinions on London and the royal family were particularly scathing. ‘In my opinion’, she wrote to her friend Inés de la Asunción in 1607, ‘only to please God can one tolerate living here’. She called James I’s daughter, Elizabeth, an ‘ignorant slip of a girl’ and ‘the boy prince’ Charles as ‘a nasty little so-and-so in matters of religion’.

What property do you own?

I rent property and do not own any.

This is a bit misleading since Carvajal grew up in an aristocratic home. She inherited wealth and engaged in a sustained legal battle against her brother for her inheritance in the 1590s. When she won, however, she donated the money to the Society of Jesus. In London, she wrote with pride about living in poverty in a house in Spitalfields, where she and her ‘warrior maidens’ made ends meet by making gold embroidery thread, typically used in Spain for religious vestments. She also created relics made from the bodies of executed priests, preserving their bodies in her household in East London and sending them to various patrons and clients in gold and silver boxes.

What is the main thing you do to earn a living?

James I himself referred to Carvajal as a ‘foreigner’ and a ‘spinster’, but I am going to go with, I work in a profession, such as a lawyer/academic/clergyman/writer/clerk. Carvajal had a profound sense of religious vocation, which she devoted her life to while choosing not to become a nun.

What positions of office or authority have you held?

I hold a position in a stranger church and/or hold an influential place among immigrant craftspeople.

Technically, Carvajal didn’t hold office. But she firmly believed her misión de Inglaterra was conferred onto her by God, connecting her evangelism to missions happening in other parts of the world. As a result, she possessed a keen sense of divinely-appointed authority. ‘In the session of the Council of State’, Carvajal wrote to the Duke of Lerma, the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbot had brought forth the accusation that ‘I have brought many Protestants to my religion by means of persuasion’.

How much are you worth?

I’m going to tick the lowest amount, under £20, though this is reflects Carvajal’s wealth in London, rather than her upbringing in Pamplona, Valladolid, and Madrid.

What is your living situation most comparable to?

I have some furnishings including a table, some stools, and some earthen pots; I have tools for my trade; I have just enough to get by some months and plenty in other months; if I get ill then I will need to depend on charity. All of my furniture is old and inherited and I cannot afford to buy any new pieces.

When Carvajal was arrested in 1608, she used her shabby clothes as evidence of her commitment to the cause, recording that during the interrogation ‘my sleeve, on which all the light was falling, had a mended spot or two showing, and on my head was a ragged black taffeta’.

Credit in the community

I struggle to get by through my work and am dependent on charity.

Carvajal’s charity came from high places, and she was well-connected, having access to the households of Catholic ambassadors in London. She also provided some relief to imprisoned Catholics before their execution, offering to pray with them and bringing them pear tarts.

What kind of people are in your close social circle?

The lord/lady of the manor; a lawyer, town or court clerk, an author, a clergyman; other tradesmen or shopkeepers in my locale or their wives; other servants who work in the houses on my street; financially secure wives and widows.

Carvajal interacted with a range of men, women, and children from different social statuses. She learned English with the help of two ‘ladies form the land’ and offered spiritual guidance to prominent English Catholics. Once comfortable with the language, she publicly preached in the streets of London. She visited priests in prison, ambassadors, and complained about the ‘false bishop’ Abbot and other Jacobean councillors who sought to restrict her efforts to convert. She also corresponded with high-ranking courtiers in Spain, including Philip III’s favourite, the Duke of Lerma.

Status…

Professional middling

The calculator has placed Carvajal as ‘professional middling’, ‘defined by your high level of literacy’. This seems accurate in terms of the kinds of connections and spaces that Carvajal moved through: a kind of ‘golden mean’ between her aristocratic upbringing and her fervent rejection of wealth and comfort in the second half of her life. It places due emphasis, too, on her strong sense of vocation through her spiritual work, including her language-learning skills. But this useful exercise also raises attention to what thrums beneath social categorization, from the influence of personal choice (in this case, downward mobility) to the way migrant women sought to find a place in drastically different environments from those they called home.

Bibliography

Anne J. Cruz, The Life and Writings of Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza (Toronto: Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2014)

The Letters of Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza, Volume I, ed. Glyn Redworth (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2012)

Glyn Redworth, The She-Apostle: The Extraordinary Life and Death of Luisa de Carvajal (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

This Tight Embrace: Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza (1566 – 1614), ed. Elizabeth Rhodes (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 2000)

The Turkey Merchant’s Daughter

By Emily Stevenson

Joan Staper was born on 24 November 1570 at 6:30 pm to Richard and Dionis Staper. Her father, one of the most important English merchants in the sixteenth century, was deeply invested — financially and personally — in the Anglo-Levant trade, which brought vast quantities of luxury goods into England. Her mother was a member of another mercantile family, the Hewitts, and Joan would make a similar mercantile marriage to Nicholas Lete, another merchant involved in the Levant trade.

In many respects, Joan’s life was entirely typical of her social circle, atypical only in that an unusual number of details — such as the exact time of her birth — have been preserved. These details are recorded thanks to her many visits to Simon Forman and Richard Napier between 1597 and 1622.[1] Joan’s visits addressed a wide range of questions including: whether she was pregnant, whether her husband’s ship was likely to return soon, whether her daughter could be convinced to marry her mother’s choice of spouse, and which member of her household had stolen her wedding ring. These records give us access to a level of quotidian detail which makes it possible to place Joan on the calculator.

Do you have a coat of arms/Where did you get this coat of arms?

Yes, I was awarded it in my lifetime

Both her husband and father had coats of arms: Lete’s were awarded in 1616 and Staper’s appear on his monument in St Helen’s Bishopsgate, apparently awarded during his lifetime.[2]

Can you write?

I can write, but little writing in my hand survives

Joan was able to write, evidenced by a note in the Casebooks that ‘Mres Leate sent […] a letter in the behalf of her daughter [J]ane who hath for this twelfemonthe bene troubled w[ith] a swelling’.[3] There is, however, no other known evidence of Joan’s ability to write, nor extant examples of her writing.

What property do you own/What is the main thing you do to earn a living/ What positions of office or authority have you held?

I own and/or lease the building/rooms I live in/I live by the finances of my husband (but that doesn’t mean I don’t do any work!)/I have never held office

Joan lived by the finances of first her father, then her husband in property that the men owned and, typically for a woman, never held local office.

How much are you worth?

£500+

The exact details of Joan’s finances are difficult to ascertain, since she does not seem to have left a will. From her husband’s will (written after her death, since Joan is not mentioned), they appear to have been wealthy without living extravagantly. He left 1000 marks in 1631 to each of their three daughters: this comes to around £666 each (according to the National Archives Currency Convertor), which places the family well over the £500+ limit.

What is your living situation most comparable to?

I have a very large home […]

The absence of Joan’s will makes this question difficult to answer, and her husband’s will divides the estate equally between his sons without any specific mention of items. One exception is the portrait of Nicholas ‘in oyle colour’ given by their sons after his death to the Ironmongers’ company, ‘to remain in the Hall as a remembrance of their dear deceased father’.[4] The artist is not named in the records, suggesting that they were a local rather than immigrant artist. There are similar glancing references to luxury goods in the Casebooks: Joan gave Napier ‘succet & a night cap of silke’ brought back by her husband’s ships in return for his services.[5] There is no indication, however, of the family acting as literary patrons, while Nicholas’ failure to apportion expensive items such as furniture or fabrics amongst his children suggests that this was not where the Lete family invested their wealth. The second category — ‘I have a very large home […]’ — thus seems the most fitting.

Credit in the Community: which statement is comparable to your situation?

I have a fair amount of spare money to spend at my leisure

Joan’s level of financial credit is unclear: something between ‘a fair amount of spare money’ and the ability to ‘spend at will’. The constant anxiety regarding ships expressed in the Forman and Napier casebooks suggests that it would be more accurate to err towards the former, as a considerable amount of capital was tied up in ships and ventures.

What kind of people are in your close social circle?

Prominent tradesmen and their wives [OR] Financially secure wives and widows [OR] Wealthy merchants or their wives

Joan’s social circle definitely included the wives of prominent tradesmen, wealthy merchants and financially secure wives and widows — many of them related to her.

Status…

Upper Middling

The social status calculator, using these answers, places Joan in the ‘Upper Middling’ category. This tracks with her family’s level of wealth and their social status, and also usefully recognises that though merchants held considerable influence, it was not necessarily through inheritance such as a title or land. Joan’s marriage to Nicholas Lete is one example of a common way in which wealthy mercantile families attempted to circumvent this issue: her sisters made similar marriages, all serving to embed the Staper family deeper into the web of London’s mercantile family networks and ensuring the continuation of their influence after the death of their patriarch.

Using the calculator for Joan also highlights some of the difficulties of tracking the social mobility of mercantile women in the period. Though the most personal facts — when was she born, whether she could write, what she worried about — are available to us thanks to the records of her conversations with Napier, questions of finance and property are more difficult to answer because Joan was financially dependent on male figures all her life and did not leave a will. Her level of personal choice in these matters is impossible to know, since it was not recorded, and there lies a tension in trying to fit facts to answers when Joan’s presence is only inferred. Social mobility was vital to Joan’s social role — and for other merchant women as well — and this fluidity also means that her social status at the end of her life may have been different to its beginning, making the calculator result primarily significant for her later years. It remains a useful exercise, however, with the ‘Upper Middling’ category recognising the importance of gaining and maintaining social status for such merchants, as well as the potentially meteoric changes in fortune resulting from participation in England’s growing trade networks.

An Englishman in Italian

by Tom Roberts

How will the Social Status Calculator place a London-born son of Italians and self-described ‘Englishman in Italiane’? Meet John Florio, the linguist, translator, and celebrated translator of Montaigne whose career as England’s champion for Italian cultural consumption brought him from the cramped lodgings of a French silkweaver to the Privy Chamber.

What is your gender?

Male

Do you have a title like Sir, Duke, Duchess, Princess, etc.?

No

Do you have a coat of arms?

Yes

A marigold with the sun in chief.

Can you write?

I write regularly, though not just for professional/trade purposes

Writing was of course central to John’s career and reputation, but it was not a primary source of income in a commercial sense. His early printed Italian dual language manuals were as much (unsuccessful) attempts to secure patronage as they were functional language learning materials for an expanding middling sort with Italianate tastes. Whilst some works of translation carried out in the 1580s can be said to have been commercially driven, and his employment as reader in Italian and private secretary to Queen Anne would have involved writing and translating correspondence, John’s more distinguished and celebrated works of translation and lexicography were not financially viable in the commercial world of print, and instead required the support of wealthy and often aristocratic patrons.

What property do you own?

I own and/or lease several buildings in the community I live in

[OR]

I rent property and do not own any

The dramatic change in John’s fortunes throughout his life make this question difficult to answer. What we know of John’s property comes from his will in 1626, seven years after the death of his patron Queen Anne and the loss of his position at court, when he lived in a leased property in Fulham valued at around £6 per annum. However, it seems likely that he would have owned other properties during his more prosperous years that were then sold when the family fell on hard times.

What is the main thing you do to earn a living?

I work in a profession, such as a lawyer/academic/clergyman/writer/clerk/doctor

We can say with confidence that John worked in a profession, albeit a poorly defined one with no concrete training programme. Whilst in Oxford in the early 1580s, he worked as a tutor in Italian to interested students, although without an official university position. Returning to London in 1583, he taught Italian to the daughter of the French Ambassador, Michel de Castelnau, and translated several news items dispatched from Rome whilst possibly in the employ of Sir Francis Walsingham. As he became connected to those prominent Inns of Court men and intellectuals in the circle of Sir Philip Sidney, John caught the attention of the Earl of Southampton and the Countess of Bedford, who he tutored from the early 1590s. This financed both his first Italian/English dual language manual in 1578, and his celebrated translation of Montaigne’s Essays in 1603. Both this work and his reputation as England’s leading expert in all things Italian brough him into the orbit of Queen Anne, and the following year he was appointed her private secretary and Groom of Privy Chamber. This position came with a yearly pension, which had risen to £100 by the Queen’s death in 1619.

What positions of office or authority have you held?

I work for the government of the country (I advise the Queen, I am the chancellor or I am in charge of a royal department)

Groom of the Privy Chamber, Reader in Italian, and Private Secretary to Queen of Anne.

How much are you worth?

I don’t know

This really depends on what point in John’s life we are focusing on. Although we have some sense of his worth between 1604 and 1619, he had little financial security either side of this period. Arriving in London a migrant with no family or friends in the city, the 1570s and early 1580s were marred by poverty and unsuccessful attempts to secure patronage. As he became well acquainted with the intellectual circles around Oxford, the Inns of Court, and the French Embassy, he found relatively steady employment as a language tutor and translator. How much this paid is unclear, although he relied heavily on the generosity of Nicholas Saunders, a gentleman from Surrey, for several years before eventually coming to the attention of Southampton and Bedford. Patronage was of course an unreliable income, and even the stability he attained under Queen Anne would not last. Following the Queen’s death in 1619, the pension of £100 per annum that she had reportedly promised John was denied by the Lord Treasurer. Over the next few years, his fortunes steadily worsened until his death from plague in 1626.

Few material possessions are listed in John’s will – he bequeaths his daughter, Aurelia, her deceased mother’s wedding ring, which was regrettably the only thing of any value he had to give by ‘reason of my poverty’. This was not strictly true. He had collected some ‘Three hundred and Fortie’ Italian, French, and Spanish language books by his death, which he bequeathed William, Earl of Pembroke, to place in his library at Wilton or Baynards Castle as a ‘token of my service and affection’. He also left Pembroke a curious jewel described as a ‘Corinne stone’, gifted to his late benefactor the Queen by Ferdinando de’ Medici, Duke of Tuscany. He also kept several other items items gifted him by his former employer, including a ‘Faire blacke velvet deske, embroidered with seede pearles, and with a silver and guilt inkehorne and dust box therin’, which he left to his son-in-law, James Mollins; and two ‘oule greene velvett deske with a silver inke and dust box in each of them’, which he gifted to his ‘much esteemed, dearely beloved, & truly honest good Friends’ Theophilius Field, Bishop of Landaffe, and Dr Richard Cluet, vicar of Fulham.

There was clearly some financial dispute between John and Aurelia. She claimed he owed them ‘threescore pound’, although John claimed that ‘my conscience telleth mee, & soe knoweth her conscience, it is by Thirty Foure pound or therabouts’, plus a separate loan from James of £10 for which two gold rings encased with thirteen diamonds (another gift from the Queen) was given up as collateral. John proposed that they accept the rings, which ‘I might many tymes have had forty pounds readie money’, several other items, and the lease of his house in Shoe Lane as payment.

What is your living situation comparable to?

I’m young; live in accommodation owned by my employer, college or inn; I am starting to build up things pertinent to my trade; I’m always learning.

[OR]

I have lots of tools/items in order to work my living; a stock of materials to use in my trade; some joined furniture including one or two special pieces with carving; perhaps a servant and an apprentice

Again, the answer depends entirely on the period. If he was the ‘Jhon Flehan’ residing with the French silkweaver Michael Barnyard in the parish of St James Garlick Hythe in November 1571, he would have lived in overcrowded conditions with many other strangers from the continent when he first arrived back in England. He appears to have secured the resources and connections to print his first dual language manual, Florio his first fruites, in 1578, although he failed to spark the interest of the dedicatee, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and a few years later he’s found residing in presumably meagre quarters in Oxford as a language tutor. From 1583, he resided in the house of the French Ambassador on the Strand. We can assume that his living situation changed after he came to the attention of the Southampton and the Countess of Bedford, and his £100 per annum salary under Queen Anne to the Queen would have given him the means to live an exceptionally comfortable lifestyle. Whether he purchased a property is unknown, and dependent on whether he was considered ‘native-English’ in the eyes of the law. He claimed English identity, but it’s likely that both his parents were first generation migrants, in which case John was, in the best-case scenario (legally speaking), a denizen. This meant that he had certain limited rights, including the right to lease property, sell merchandise, and inherit/bequeath property. Owning land or properties freehold, however, was restricted to the natural-born English.

In any case, he resided at a leased property in Fulham with his second wife Rose and servant Arthur until his death, surrounded by the tools of his trade: hundreds of books and three separate writing desks.

Credit in the Community: which statement is comparable to your situation?

I have some spare money, have the ability to borrow on credit, and can spend and take risks

[OR]

I don’t know/none of these

Clearly a man in the employ of the Queen had some standing amongst creditors, although John would often allude to anti-stranger hostility from the English throughout his work. He was also known to butt heads with others at court, and feared that some of these adversaries would discourage the Earl of Pembroke from supporting Rose after his death, pleading in his will that the Lord Chamberlain ‘not suffer her to be wrongfully molested by any enemi of myne’. For whatever reason, Pembroke’s support was not forthcoming, and other, later friendships and associations proved equally fickle. His ‘true honest good Friends’, Field and Cluet, refused his request to act as executors of his estate, and the responsibility reverted back to Rose. It is worth noting, however, that despite his professed poverty, he had no creditors worth naming in his will apart from his daughter and son-in-law.

What kind of people are in your close social circle? (check all that apply)

The lord/lady of the manor

[OR]

A lawyer, town or court clerk, an author, an academic, a physician, a clergyman or their wives

[OR]

Students at universities or the inns of court

[OR]

Other tradesmen or shopkeepers in my locale or their wives

[OR]

Wealthy merchants or their wives

Florio interacted with a range of men and women from different social statuses. He was, of course, employed by the Queen and acquainted with senior statesmen; he was patronised by well-respected families in the shires, and aided proto colonialist through works of translation. He caroused with Inns of Court men, a close friend of the Welsh preacher Matthew Gwinne and the poet, Samuel Daniels, marrying his sister in 1580. Ben Jonson gifted a copy of his 1605 play, Volpone, in which he referred to Florio and ‘his Loving Friend … the ayde of his Muses’. He maintained correspondences with renegade recusants, like Theodore Diodati, exchanged ideas with heretical ex-Dominicans, like the cosmologist Giordano Bruno, and was acquainted with London’s community of wealthy Italian merchants and financiers.

Status…

Profession-al Middling

The calculator has placed Florio as ‘professional middling’. He possessed a ‘high level of literacy’, was exceptionally mobile, and relied on his ‘social networks with the landed gentry, urban gentry, and middling officeholders’. It was a difficult task as John’s fortunes changed greatly over the course of his life, and he did not, as did many his contemporaries, set up shop in London teaching Italian to aspiring courtiers, and English to resident Italian merchants, but navigated his way through the English social hierarchy by forging a place for himself at a prominent intersection – the interest in and admiration for Italian culture. Strikingly, it suggests that if property ownership factors into our assessments of social status, we inevitably exclude a substantial number of first- and second-generation migrants who were exceedingly wealthy and well connected, but unable to own property freehold. For Florio in particular, who capitalised on his Italian heritage to assert his authority as London’s preeminent advocate for Italian language and culture, difference meant both his exclusion from traditional social and economic systems and his inclusion in a vast intellectual network that resulted in a singularly impressive career.

Bibliography

‘Will of John Florio of Fulham’, 1 June 1626, TNA, PROB 11/149/289

Florio, John, Florio his firste fruites which yeelde familiar speech, merie prouerbes, wittie sentences, and golden sayings (London, 1578; STC (2nd ed.) / 4699)

Florio, John, Florios second frutes to be gathered of twelue trees, of diuers but delightsome tastes to the tongues of Italians and Englishmen (London, 1591; STC (2nd ed.) / 11097)

Florio, John, Queen Anna’s nevv vvorld of words, or dictionarie of the Italian and English tongues, collected, and newly much augmented by Iohn Florio, reader of the Italian vnto the Soueraigne Maiestie of Anna, crowned Queene of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, &c. (London, 1611; STC (2nd ed.) / 11099).

Pfister, Manfred, ‘Inglese Italianato – Italianato Anglizzato: John Florio’, in Renaissance Go-Betweens: Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Andreas Höfele and Werner von Koppenfels (Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co, 2005)

Wyatt, Michael, The Italian Encounter with Tudor England: The Cultural Politics of Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[1] Digitised as part of the Casebooks project, <https://casebooks.lib.cam.ac.uk>.

[2] ‘ARMS OF NICHOLAS LEATE. From Camden’s Grants, Hart. MS. 6095’, printed in Joseph Leete, The Family of Leete (London: Blades, East & Blades, 1906), p. 189.

[3] Case50684, <https://casebooks.lib.cam.ac.uk/cases/CASE50684> (accessed April 2020).

[4] The Family of Leete, p. 188.

[5] CASE41692 <https://casebooks.lib.cam.ac.uk/cases/CASE41692> (accessed March 2021).